FRANK FENNER WW2

On this page

Enlistment in the Australian Army Medical Corps

Military Training at Woodside

Service in Palestine

2/1 Casualty Clearing Station

Australia, April 1942 to March 1943

Pathologist, 2/2 Australian General Hospital

Malariologist in New Guinea

Other Research in New Guinea

Wartime Work at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

Marriage

Service in Morotai and Borneo

Appointment as Francis Haley Research Fellow

Leave Prior to Discharge

Discharge from the Army

References

This is a chapter from a book by Frank Fenner Nature, Nurture and Chance: The lives of Frank and Charles Fenner,The War years, May 1940 to February 1946 Chapter 3, ANU E press, 2006, Canberra. Frank was malariologist during WW2 and served with the 2/6th Field Ambulance. Frank has given his permission for this chapter to be place on the SA website. Enlistment in the Australian Army Medical Corps As early as December 1939, it had been decided that Australian troops would initially be sent to Palestine, and the advance party had arrived there in early January. I knew that a number of unusual infectious diseases that occurred in tropical and semitropical countries were found in the Middle East, and I wanted to have the chance to be something other than a regimental or field ambulance medical officer. In 1939, resident medical officers at Adelaide Hospital received board and lodging and about £5 a week, plus a bonus of £200 if they stayed on for the full year, i.e., until February. I used the bonus to go to Sydney and study for the Diploma of Tropical Medicine (DTM), a three-month course available in Australia only at the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine at the University of Sydney. I stayed at St Andrew's College, which was on the University grounds. My best friend there was Edgar Mercer, who had been at Adelaide High School a couple of years ahead of me. He had a flat in King's Cross and we used to go there most weekends. Coming from Adelaide, which has hot but dry nights, I found Sydney's humid nights during February hard to take. I worked for three months at the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, where, amongst others, I met Ted (later Sir Edward) Ford, who was lecturer in bacteriology. He had been a close personal friend and admirer of my mentor in physical anthropology, Wood Jones, and Ted and I were later to work as colleagues in malaria control in New Guinea. While there I also played for the Sydney University hockey team. Altogether, I greatly enjoyed my time there. Returning home to Adelaide in April, I finally enlisted as a captain in the Australian Army Medical Corps on 9 May, 1940, commencing duty with the 2/6 Australian Field Ambulance on 12 June, 1940. During the six-month training period at Woodside, in the Adelaide Hills, as well as all the other training, we used to go for long marches every few days, during which I used to read a book as soon as we got going, an uncommon but not illegal action. The longest march we had was from Woodside to Mannum, where we officers met with the local doctor, whose name was Alpers. I remember meeting his two sons, one of whom, Michael, eventually became the Director of the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research. In recent communications with Michael, he also remembers my arrival there. We usually had weekends off and most of us would go back to Adelaide. I continued playing hockey with the Adelaide University team, and one day was hit in the eye by the ball and got a black eye. As might be expected, this aroused a lot of derisive comment from the troops at drill on Monday. In our spare time, Noel Bonnin (a surgeon six years older than me and also an officer in the 2/6 Field Ambulance) and I set up a small laboratory and carried out a number of experiments on the treatment of gas gangrene in guinea pigs by the local application of sulphanilamide, the only antibacterial drug then known. We published an article describing our results (Bonnin and Fenner, 1941). An article in the Adelaide newspaper, The News, in January 1942, mentioned that research workers at Tulane University, in the United States, had published a paper suggesting the use of another sulphonamide, sulphathiazole, based on our results.

Figure 3.1. Officers' Mess, 2/6 Field Ambulance, Woodside, September 1940 At head of table: Colonel R. Southwood (ADMS, Southern Command), on his left, Lieut-Col. E. H. Beare, Commander of the Unit. First on left of table, Frank Fenner; others include R. S. Wilkinson, R. Sands, N. J. Bonnin, F. K. Mugford, W. M. Irwin, J. R. Magarey, H. M. Fisher, R. A. Higginson, D. W. Sands, and C. G. Rankin. Along with many other troops, the Unit embarked for Palestine in December 1940, disembarking at Suez. We then moved up to Gaza, where the majority of Australian troops were located immediately after they arrived. A field exercise there a few weeks after disembarkation included an exchange of officers and other ranks between the 2/4 and the 2/6 Field Ambulances, during which I earned the wrath of the brigadier in charge of the operation. As far as I could ascertain, he was upset because I had followed the advice of the Officer-in-Charge of the 2/6 Field Ambulance, Lieut-Col. E. (Teddy) Beare, that officers should always march with the men. Thus, I left the decision about where to place an Advanced Dressing Station to the Staff Sergeant, who had gone ahead with the equipment on a truck. The brigadier arrived at the same time as I did, regarded the site that had been selected as very dangerous, and rightly blamed me for it. During that exercise we had the opportunity to visit many Palestinian villages, and see the threshing of wheat, camels at work, and so on. I still feel sympathy for the Palestinians ousted by the state of Israel. A few weeks after this exercise I was transferred to Headquarters, First Australian Corps, where I worked closely with the Deputy Director of Medical Services, Brigadier W. W. S. Johnson, a fine physician and a fine gentleman. There may have been other considerations in my transfer, possibly related to my Diploma of Tropical Medicine, but for me it was a most fortunate change. Johnson took me with him when he visited Jerusalem and there I met Dr Saul Adler, FRS, an outstanding parasitologist and an expert on malaria in the region. I met Ted Ford again, he was responsible for a Mobile Bacteriological Unit attached to Corps headquarters. I also made the acquaintance of Colonel (later Brigadier Sir) Hamilton Fairley, Director of Medicine for the Second AIF, and Colonel J. S. K. Boyd, Director of Pathology for the British forces in the Middle East, both outstanding experts in tropical diseases. Neil Hamilton Fairley, 1891;1966 Born in Melbourne in 1891, Fairley graduated MB BS with first class honours from Melbourne University in 1915. In 1916, he enlisted in the Australian Army Medical Service and sailed to Egypt as pathologist to the 11th Australian General Hospital. He was subsequently promoted Major and, in 1918, at the age of 27, was appointed Senior Physician to the Hospital, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He returned to Melbourne in 1920 as first assistant to the Director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, but in 1922 went to Bombay, where he worked on schistosomiasis, dracontiasis and sprue. From 1925 to 1929 he worked again at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, studying snakebites and snake venoms. In 1929 he went back to London as lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where he worked on filariasis, leptospirosis and malaria. With the outbreak of World War II, Fairley enlisted again in the Australian Army Medical Service, with the rank of Colonel, and joined the Headquarters of the Australian Forces as Consulting Physician. I met him when he visited 2/1 Casualty Clearing Station in Nazareth. Returning to Australia in 1942, he was promoted to Brigadier and became Director of Medicine in the Australian Military Forces and Chairman of the Combined Advisory Committee on Tropical Medicine, South Pacific Area, and as such, directly responsible to General MacArthur. His major contributions in this role were ensuring that all available sulphaguanidine was made available to troops on the Kokoda Track, where dysentery was undermining their fighting capacity, and the setting up of the Land Headquarters Medical Research Unit (LHQMRU) in Cairns in June 1943. The latter consisted of an entomological section, which was sent 20,000 anopheline larvae from New Guinea weekly, a pathology section, and a clinical section, which supervised the use of human volunteers subjected to infection with falciparum malaria. Boyd (1966) notes that the keynote of success in all these experiments was the subinoculation test, which was carried out by my wife, Bobbie. After the War, Fairley became Wellcome Professor of Tropical Medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and followed up the experiments on the pathogenesis of malaria, but in 1948 he had a serious illness from which he never fully recovered. He continued to serve on many committees, but in 1962 retired to the country and died in 1966 (see Boyd, 1966). Fairley, who had worked on malaria in Macedonia before the War, advised the Commander-in-Chief, General Wavell, not to send British and Australian Troops to Macedonia, a highly malarious area, to bolster Greek resistance to a German attack, as he had planned, but rather to send seasoned Greek troops. Wavell reacted violently, but after an interview he withdrew his criticisms. Knowing from our conversations in Nazareth that I had a Diploma of Tropical Medicine, he dispatched me to a staging camp in Alexandria to await shipment to Greece as a malariologist for the Australian forces. I was there, in a very dusty staging camp, for about five weeks. During this time I explored Alexandria, including the catacombs, where I met a South Australian anthropologist who was studying the burials there, and made friends with some very interesting local people. However, after about five weeks it became clear that the German stukas (dive bombers) were overwhelming the Allied forces, and my only participation in the Greek campaign was to go to Crete as medical officer on a ship evacuating civilians, some weeks before the German parachutists invaded the island. We returned to Alexandria with an imposing naval escort. Shortly after I had returned to Corps Headquarters, I was transferred as a physician to the 2/1 Casualty Clearing Station (2/1 CCS), which was located in Nazareth as a field hospital for Australian soldiers involved in the Syrian campaign, which was developed to oust the Vichy French, who then occupied Syria and Lebanon. Since many of the patients suffered from malaria or dysentery, I set up a small laboratory and carried out malaria diagnosis by examination of thick films. While there, my colleagues called me Noffie (an abbreviation of Anopheles, the malaria mosquito), a nickname that stuck until I moved to New Guinea as a malariologist. At the conclusion of the Syrian campaign, the Unit moved to Beirut, where it set up in what was said to have been the only mental hospital in the Middle East, at Asfurieh, about 20 km to the east of Beirut. We were there for six months. I made friends with an American microbiologist who worked in the American University in Beirut, and also with a well-to-do Lebanese family named Hitti, with whom I spent several very pleasant weekends at their country home in the mountains. During this period Professor Sydney Sunderland, who had succeeded Wood Jones as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Melbourne, entered into negotiations with me and the Army authorities in Australia to secure my release, so that I could return to Australia and take up the position of Senior Lecturer in his department. I replied saying that my current commitments were such that I could not accept his offer, but that I looked forward to joining him after the War. However, after my experience with malaria in New Guinea (see below), I had decided that research in infectious diseases, not anatomy or physical anthropology, was to be my post-war activity. I therefore did not respond to a later invitation from the University of Adelaide to apply for the vacant chair of anatomy. My friend, Noel Bonnin, who was by then a surgeon in 2/1 CCS, and I also arranged two very interesting trips from Beirut during two separate periods of leave. For the first, we hired a taxi with a driver who spoke French but no English, and our French was very primitive. Noel acquired two four-gallon tins of petrol from friends in a nearby British Field Ambulance, and we travelled south through Haifa, Jerusalem and Jericho, bathed in the Dead Sea and went on into Jordan. We stopped at Jerash, a wonderfully well-preserved Roman city, then proceeded through Amman, the capital of Jordan, and south through the desert until we came to a narrow gorge to Petra, the rose-red city half as old as time, and spent a day exploring the wonderful buildings carved out of the red sandstone. Unaccustomed to travelling over corrugated desert roads, which we had to use on our trip down, our driver drove slowly, while with our experience of travelling on corrugated roads in outback Australia we tried to encourage him to drive faster. We came back along the mountains that form the western shore of the Dead Sea. Here our driver felt at home (from his experience in the mountains of Lebanon) and drove so fast around the winding roads that we shouted Lentement! Lentement!to no avail. We visited some impressive castles on the mountains, and eventually stopped off in Damascus, then visited Homs, and back to Asfurieh. My next adventure, with two medical orderlies and in a field ambulance, was to accompany a regiment of the 9th Division from Palestine through Egypt to Mersa Matruh, in Libya. This passed without incident, and I then came back at my own pace, and stopped off near the pyramids in Cairo for a couple of days to explore that part of the world. This proved a useful preparation for my second week's holiday with Noel Bonnin. We had purchased and read a Penguin book on the wonders of ancient Egypt and, a few months later, spent a week's leave travelling by train from Beirut through Cairo and along the Nile Valley to Aswan, where a major dam was under construction, then back to Luxor, where there were an amazing number of famous ruins. Usually a very popular tourist destination, it was deserted because of the War. Knowledgeable as we thought we were, having read the Penguin book, we interviewed several guides at Luxor before selecting the one we judged to be the best. He turned out to be a splendid guide. We stayed in a luxurious but almost empty hotel and we went to all the local sites. Apart from the marvels of the ancient Egyptian ruins, there were a couple of incidents on this trip that I vividly remember, 65 years later. The first occurred on the way to Cairo. There had been a severe sandstorm in the Sinai Desert and the train ran off the line just before it reached Kantara, on the Suez Canal. The 2/2 Australian General Hospital (AGH) was located at Kantara and Noel's brother was a physician there, so we spent the night with him before proceeding to Cairo the next day. We had planned to spend a day in Cairo and, importantly, to visit the British Pay Office to get some Egyptian currency. However, we arrived a day late, in the early evening, in a blacked-out city, and the train to Aswan on which we were booked was due to leave in an hour. I thought that I could remember where the Pay Office was from my earlier trip (to Mersa Matruh), so we ran through the blacked-out city streets, arriving just as the paymaster was packing up, and got our money. Then a run back to the station and we threw ourselves into the train just before it left. The other memorable incident was our departure from Luxor. The train to Cairo was filled with British troops coming down from Khartoum. Our excellent guide ran back and forth, speaking with the railway officials, and an extra carriage was hooked onto the train for our convenience. With the entry of Japan into the War, Prime Minister Curtin insisted that all Australian troops except the 9th Division, which was part of Montgomery's force at El Alamein fighting against Rommel, should immediately return to Australia. I came back as the medical officer for a transport battalion on a small and very old ship, the Pundit, leaving from Suez on 8 February, 1942. We stopped for a week in Colombo, while many passenger ships and a protective fleet of warships was assembled. By the end of the first day at sea after leaving Colombo the fleet was almost out of sight; Pundit could not keep up. The fleet commander signalled, Goodbye, Good luck and steamed away. There were some scares about Japanese submarines, and we steamed ahead at full speed (12 knots an hour!) but, fortunately, these were false alarms. A couple of other memories of that trip were that, on the fortnightly payday, all the troops of the transport battalion would play two-up until by five o'clock all the money was redistributed, and that I read several quite substantial books, including H. A. L Fisher's 1,300-page A History of Europe. We lived on bully beef and biscuits, and I lost about a stone and a half on the trip. Finally, as I remember it, it took us about seven days to cover the last 350 nautical miles, until we disembarked at Fremantle. Looking over the side, the water seemed to be moving ahead of the ship. Pundit never left Fremantle; it was not considered to be seaworthy. From Perth troops from the eastern states took the train across the Nullabor, arriving in Adelaide on 6 April, 1942, where I took leave with the family at 42 Alexandra Avenue. The 2/1 CCS set up a small hospital at Ipswich, near Brisbane, and, soon after that, when my leave was over, I rejoined them. One day, Brigadier Fairley visited the Unit and asked me whether I would like to become a hospital pathologist. With visions of six months in Sydney for a training course, I had no hesitation in accepting. Instead, a few days later I found myself on the narrow-gauge train steaming north to Hughenden, in Central Queensland. I was the only male on the train, but there were a couple of hundred women, nurses moving up to the tented 2/2 AGH. I did not talk to any of them, but I remember seeing a particularly attractive nurse combing her long hair; she was later to become my wife. I was replacing Major (later Colonel) E. V. (Bill) Keogh, who had been pathologist there when the hospital was at Kantara, in Palestine. When the troops returned to Australia he was appointed Director of Hygiene and Pathology at Land Headquarters in Melbourne and, as such, was my boss until the end of the War. One of the surgeons at 2/2 AGH was Major Edgar King, who was appointed Professor of Pathology at the University of Melbourne at the end of the War, so my principal worry, that I did not have skills in histology, was relieved. Promoted to Major on 10 November, 1942, I worked at the 2/2 AGH for about nine months, during which time there was a constant stream of patients from New Guinea, most with malaria or dysentery. I published three papers (of mediocre quality) in the Medical Journal of Australia as the result of my work at 2/2 AGH. It turned out that the young woman with the long hair who I had noticed on the train was Sister Ellen Margaret (Bobbie) Roberts, who, in June 1945, was to receive the honour of Associate of the Royal Red Cross for her work in the 2/2 AGH blood bank (see below). There was not much demand for blood transfusions in Hughenden, and she was assigned to help me with haematology and malaria diagnosis. Major Patrick de Burgh, who was to succeed Professor Hugh Ward as Professor of Bacteriology at the University of Sydney, ran a Mobile Bacteriological Laboratory near the hospital, and he and I examined Bobbie for her skill in thick film diagnosis of malaria; she passed with flying colours. Thereafter, she worked for a few hours each day in my laboratory. On 3 December, 1942, the tented hospital at Hughenden was hit by a cyclone. Every tent was blown over. My laboratory, one of the very few wooden buildings, was tipped sideways but held up by the water pipe leading to the laboratory tap. After a few days, the tents were re-erected, but early in January the hospital was moved to Rocky Creek, inland from Cairns on the Atherton Tableland, which was high enough to be free of Anopheles mosquitoes (Anopheles punctulatus, an effective vector, was common in Cairns). Ted Ford had carried out malaria surveys in New Guinea before the War. To find out exactly what was happening in the field in New Guinea, Colonel Keogh posted him as Deputy Director of Hygiene and Pathology at Port Moresby, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. In the campaign at Milne Bay, in September 1942, relatively untrained Australian troops had achieved the first defeat of the Japanese on land; they later suffered severe casualties from malaria (quinine was ineffective as a suppressive drug against New Guinea strains of malignant tertian malaria). Early in December, Ford sought and obtained an interview with the Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Army, General (later Field-Marshal Sir) Thomas Blamey. In his quiet persuasive way, Ford convinced Blamey that, unless malaria was controlled, the army in New Guinea would be totally destroyed by the disease. Blamey acted immediately. New Routine Orders dealing with malaria, prepared by Keogh with Ford's assistance, were promulgated and enforced. To provide expert advice and dramatise the importance of malaria, three new posts of malariologist were established to supplement the work of the Assistant Directors of Hygiene. In March 1943, Ford was appointed senior malariologist, based in Port Moresby, and two other medical officers, Major J. C. English and myself, were appointed malariologists. I moved up to Port Moresby in April and initially shared an office there with Ford. In July, I moved to Buna, on the north coast, where troops were preparing for the Lae-Finschhafen campaign.

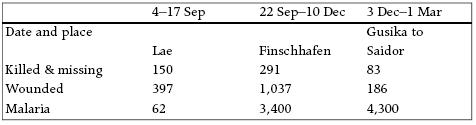

Figure 3.2. Frank Fenner at the site of the 2/2 Australian General Hospital at Hughenden a day after the cyclone Sir Edward (Ted) Ford Brian Gandevia noted, and I can confirm that Ted Ford had several personal qualities rarely seen in one man: an ever-present gentleness, a great depth of kindness and understanding, a wonderful generosity and a sincere humility, and a keen sense of humour and wit, none of which precluded determination and firmness when the occasion demanded (as was evident in his conversation with General Blamey). He was a late starter in medicine, working in the Postal Department at night and doing medicine by day. Graduating in 1932 at the age of 30, he entered academic medicine by becoming a lecturer in anatomy, where he came under the charismatic influence of Frederic Wood Jones. After obtaining a Diploma of Tropical Medicine in 1938, he investigated venereal disease and malaria in New Guinea. Back in Australia, he became a lecturer in bacteriology at the Sydney School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (which is where I first met him in 1940; in 1947 he became Director of the School) and in 1941 he went to Palestine as commanding officer of a Mobile Bacteriological Laboratory. Back in Australia, Bill Keogh organized his transfer to New Guinea as Bill's deputy, and in 1943 he was appointed to the new post of Senior Malariologist, where, of course, I had very close relations with him (see Gandevia, 1994). Jim English and I learned what our job was as we went along. By this time, quinine had been replaced by atebrin. Our first mission was to convince all those in charge of troops in the field, from colonels to platoon commanders, that they must ensure that all troops under their control swallowed one tablet of atebrin daily. I and all troops who did this became greenish-yellow in appearance, and some suffered from skin and neurological problems as complications (but not impotence, a rumour that was widely circulated among the troops). As malariologists, we also supervised the work of the Malaria Control Units and Entomology Research Units associated with the campaigns to which we had been allocated. As malaria came under better control, we took responsibility for the prevention of other insect-transmitted diseases, mainly dengue and scrub typhus, as well as malaria. Besides keeping in close touch with Keogh via demi-official letters, I had frequent contact with Ian Mackerras (then Director of Entomology and later the first Director of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research) and his deputy, Francis Ratcliffe, with whom I was later to collaborate in studies of myxomatosis. I also met our equivalents in the US Army in New Guinea, Majors McGhee Harvey and Fred Bang, both professors at Johns Hopkins University, who remained good friends in my post-war days. During this period I was instructed by Colonel Keogh to apply for the position of Director of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science in Adelaide, where Dr Weston Hurst had been Director during my intern days. Major R. J. Walsh, officer-in-charge of the Blood Transfusion Unit in Sydney, who later became a very good friend of mine, had received similar instructions; Keogh insisted that possible candidates for such positions who were in the services should not be overlooked. Fortunately, in terms of our subsequent careers, neither of us was appointed. The major campaign with which I was closely associated in New Guinea was the capture of Lae and Finschhafen by the troops of Second Australian Corps, comprising the 7th and 9th Divisions, over the period September 1943 to March 1944. I wrote a long technical paper on malaria control during this campaign, which is summarized in A. S. Walker's history of medical aspects of the War (Walker, 1952). I set out below an abbreviated version of Walkers summary: The terrain was highly malarious; the military operations were highly successful. This campaign began with better prospects than others previously fought. Equipment was better, protective clothing was worn, mosquito repellent and atebrin were available, and mosquito control was applied at an early stage in the operations, the control units moving along with the troops Notwithstanding all this nearly 10,000 men were evacuated with malaria. There was no question that the malaria risk was high in Lae and Finschhafen; the Japanese suffered heavily, 308 died out of 708 admitted to one of their field hospitals in the Huon Gulf area. Conditions were favourable for survival of adult mosquitoes long enough to enhance the risk of a rising infection rate. It was most important to realise that poor antimalarial discipline increased the risk of a gametocyte reservoir among the Allied troops. In Lae and Finschhafen control of adult mosquitoes was ineffective; in Lae gametocyte carriers were promptly segregated, with the result that larval control was rapid and effective, whereas in Finschhafen this segregation was ineffective and larval control was consequently slowed. The malarial risk was high during the first month after the landing, and it was only after this that control reduced the risk. Fenner made an analysis of the capture of Lae, the capture of Finschhafen and the enemy counter-attack, with the following offensives on Sattelberg and Wareo, and the final capture of the Gusika-Wareo line. Though allowances must be made for the different nature and intensity of these actions, the sick wastage figures given in Fenner's report are most significant, as seen in the table below.

Walker goes on to analyse the relative importance of other factors, such as the length of service in New Guinea, the physical condition of the troops on arrival there, the severity of the fighting, and the provision of reinforcements. Award, Member of the British Empire One (to me) unexpected outcome of my report was decoration with the Member of the British Empire (MBE) award in 19 July, 1945, on the recommendation of Colonel G. W. G. Maitland, DDMS, 2 Aust Corps. The citation read: Major Fenner has been Malariologist attached to NEWGUINEAFORCE, and has been responsible for the coordinated control of malaria throughout those areas of PAPUA and NEW GUINEA occupied by Australian troops. In the Technical Administration of the Malaria Control Units he has exhibited a devotion to duty exceeding that normally required of an officer and has contributed to the scientific knowledge of malaria control in the Army. Through the coordinated functioning of the Malaria Control Units under Major Fenners administration and the improved anti-malaria discipline in the Force, the incidence of malaria in the troops is now reduced to a minimum. While I was in New Guinea and later in Morotai, but not involved in campaigns, I became interested in severe enteric fever that occurred amongst New Guinea natives, Japanese prisoners and Australian troops in New Guinea. With the cooperation of Dr Nancy Atkinson, an expert on Salmonella bacteria working in Adelaide University, who identified the causal organism as S. blegdam, I wrote a paper on the disease among Australian troops (Fenner and Jackson, 1946) and another on cases among the New Guinea natives (Jones and Fenner, 1947). Bill Keogh Esmond Venner (Bill) Keogh was a remarkable man. I am only one of many whose lives have been greatly influenced by his actions behind the scenes. Initially enlisting in November 1914 as a non-combatant soldier in the Third Light Horse Field Ambulance and serving in Gallipoli and Egypt, in 1916 he transferred to the Third Australian Machinegun Battalion and served in France with such courage that he was awarded a Military Medal (MM) and a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). During the World War II, when he had to wear his decorations on his jacket, he would insert that part beneath his lapel. After World War I, he initially worked as a dairy farmer, then in 1922 he embarked on a medical course, graduating in 1927 with first-class honours in medicine. He wanted a laboratory job, and joined the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories in May 1928. After travelling about Australia a good deal, in 1935 he established a small research unit at the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and also worked for a time with Burnet at the Hall Institute. Bill was in the United States in September 1939, and returned immediately to Australia and was gazetted as a major in the Royal Australian Medical Corps on 13 October, 1939. On 14 February, 1940, he sailed as pathologist with the 2/2 Australian General Hospital, initially to Gaza, moving in November to Kantara, where he remained until the hospital moved back to Australia in February 1942. He was immediately moved to Army headquarters at Victoria Barracks as a full colonel and Director of Hygiene, Pathology and Entomology. As well as all his official duties, which included appointing me as pathologist and then as a malariologist to 2/2 Australian General Hospital, he played a major role, with Brigadier Fairley and Ted Ford, in establishing the LHQ Medical Research Unit in Cairns, with the specific mission of developing effective antimalarial drugs (see Gardiner, 1990). At the conclusion of the Lae-Finschhafen campaign, the Seventh Division was withdrawn to the Atherton Tablelands and I also went back, by air. Because there were very few people aboard the plane, the pilot let me have a short spell at the wheel. My memory of that was a realisation that even slight movements of the controls would result in surprising changes in altitude. I arrived back in Townsville in August 1944, staying at the 2/2 AGH but pursuing my own work. Colonel Keogh had arranged that I should come down to Melbourne for six weeks from October and work at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, where Macfarlane Burnet was now the Director. I thought it best if I could bring a small problem with me, and took advantage of the fact that an old Adelaide University colleague and friend of mine, John Funder, was working there on a newly discovered variety of typhus, a rickettsial disease called North Queensland tick typhus. This had been discovered by doctors working at 2/2 AGH while I was in New Guinea (Andrew et al., 1946). Before going down to Melbourne, I therefore worked in the field with staff of a Malaria Control Unit and an Entomology Research Unit to collect sera and ectoparasites from a range of wild animals in an effort to discover the reservoir of this newly-discovered zoonotic disease, and I took this material to Melbourne for testing. At the Hall Institute I carried out complement fixation tests on these sera, using an antigen prepared from yolk sacs infected with the North Queensland tick typhus rickettsiae. Eight animals, of five different species, gave positive results; five of the positives came from a localized area of rain forest, which was also the site of infection of several human cases (Fenner, 1946). I later found that Keogh had suggested to Burnet that this would be an opportunity for him to decide whether he wanted to recruit me as a research worker at the end of the War (see below). Captain Bobbie Roberts, as she was then, had been sent from the 2/2 AGH to the Heidelberg Military Hospital in Melbourne for the period 8 September to 8 December, 1944, to give classes on blood transfusion. This overlapped with my spell at the Hall Institute. Almost immediately after I arrived in Melbourne, I proposed to her in a little room at the Heidelberg Hospital. Since she was a Roman Catholic and I was an atheist, I was given a lecture by a Catholic priest . Three days later, we were married in a side chapel of the Catholic Cathedral, with a former laboratory assistant of mine, Lieutenant Mavis Freeman, and Bobbies closest friend, Nurse Reuben Warner, as witnesses. Major Kevin Brennan, an officer in Keogh's section at Victoria Barracks, kindly let us live for three weeks in his house, which was vacant at the time. Reflecting the religious intolerance then common in Adelaide, my mother was initially very upset that I should marry a Catholic but, after they became acquainted, they became very close friends. My father, on the other hand, wrote her a warm letter, saying that Life is too short, and too full of pitfalls, to waste any opportunity of happiness. I returned to Atherton on 24 November, Bobbie went to the LHQ Medical Research Unit in Cairns on 8 December. This Unit had been set up by Brigadier Fairley to test antimalarial drugs on human volunteers and Bobbie had already worked there, as had several physicians at 2/2 AGH. She was the only person locally available who could carry out direct blood transfusions from artificially infected volunteers to other, uninfected volunteers. She did this by using a device invented and given to her by Dr Julian Smith, who was father of the senior surgeon of the 2/2 AGH. She also assisted Major Josephine Mackerras with entomological work. I used to drive from the Tablelands to Cairns every weekend and stay with her in one of the local hotels. We studied Ideal Marriage by van de Velde (one of the few sources of such information at the time) to learn more about sexual pleasures. Colonel Talbot, the Commanding Officer of 2/2 AGH, very kindly offered us use of his holiday home at Yeppoon, then a beautiful and almost uninhabited settlement on the coast, for a honeymoon. We spent a blissful few days there, and then I received a message that I had to be in Townsville by 6 April to embark on the General Butner to go to Morotai, in the Halmaheras. Just before I embarked I met with Bill Keogh and he told me that Burnet intended to offer me a job when I got out of the Army.

Figure 3.3. Photograph of Bobbie Roberts in 1942, by Julian Smith In June 1945, Bobbie received the award of Associate of the Royal Red Cross. Her citation reads: WFX1536 Captain Ellen Margaret Fenner Sister Fenner commenced duty with 2/2 Aust Gen Hosp and embarked for overseas service on 30 Apr 40. At El Kantara she did outstanding work as Sister-in-charge of acute surgical wards and blood bank centre. She assisted the medical staff in carrying out research work and her work at all times has been brilliant and untiring. On return to Australia she carried on with the work in the blood bank when the hospital was established in Queensland. In early 1944 she was detached for duty with a Malaria Control Unit. She showed exceptional ability for this kind of work and her work was outstandingly good. Because of her work with this unit it was requested that she should be posted to the LHQ Medical Research Unit where she is at present serving. I disembarked in Morotai on 16 April, 1945. While I was on the ship and overseas, Bobbie and I wrote to each other every day. I was not able to keep her letters but, unbeknownst to me, she kept all of mine, organized by the month and tied together in neat bundles kept in a drawer next to her bed. I became aware of them when she was in bed with advanced pulmonary secondaries from a colon cancer. When I found her reading one, in October 1995, she looked at me with an expression of such deep love that I could not bear to read the letters, until October 2001, when I undertook to update my Basser Library archives. They are pretty torrid love letters, but mention facets of my scientific career not available elsewhere. The catalogue of my Basser Library archives contains explanatory notes as well as the letters. For the rest of the War, until 27 August, 1945, I was based at 1 Aust Corps Headquarters on Morotai, and was involved with malaria control in the attacks on Brunei Bay, Tarakan and Labuan. Throughout these campaigns, the malaria rates were very low, with only 97 cases being admitted to medical units between April 6 and September 7, from a force of 17,000. After hostilities ceased, I visited Brunei, Labuan, Tarakan, Balikpapan and Sarawak. With Francis Ratcliffe, I organized some trials of mosquito control by dispersion of DDT from aircraft. As reflected in my letters to Bobbie, there were long periods of boredom and anxiety about the job with Macfarlane Burnet at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Eventually, on 10 July, 1945, I received a letter from Burnet. The relevant part read: The establishment of the Chair of Experimental Medicine [at the University of Melbourne, specifically for Burnet] has made it possible for me to look forward to having a full time senior man [on a Francis Haley Fellowship] in that department. The primary interest is epidemiology in the broad sense it must be concerned with cancer, T.B. or other widespread and important human diseases. Would you be interested in a preliminary offer of such an appointment at a salary of £1000 p.a. to start as soon as your release from the Army? You would have a very considerable latitude in regard to choice of a particular field. There is a specially good opportunity in experimental epidemiology for the study of a virus disease (ectromelia of mice). In January last we found that this disease was antigenically almost identical with smallpox and vaccinia. The disease is spontaneously infective for mice. Any appointment would, of course, be subject to University approval. I had no problem in replying immediately, noting that, as far as release from the Army was concerned, I should be in the first group, having had five years service. On 30 July, I received a reply from Burnet and a request to should send him a curriculum vitae and list of published work, hoping to satisfy the University that advertisement was unnecessary. On 27 August, I received a letter from Burnet confirming my appointment as Senior Haley Research Fellow in the Department of Experimental Medicine of the University of Melbourne, on a salary of £1000 p.a. Bobbies mother had been quite ill and, on 1 August, 1945, Bobbie was transferred to 110 Perth Military Hospital, so that she could be near her. She stopped in Adelaide for a few days on the way over and stayed with my family. With the war over, and because my father was also ill, on 27 August, 1945 I was granted seven days compassionate leave and 32 days annual service leave. On 28 August, I flew from Morotai to Brisbane and, on my way by troop train to Adelaide, I met up with Ted Ford in Sydney, and had dinner with Mac Burnet and his wife Linda in Melbourne. He said everything was going well as far my appointment was concerned, but that the University had not yet decided whether the position should be advertised (in fact it never was). He also mentioned that Ian Wood, who had been senior physician at 2/2 AGH and in charge of the blood bank there, was to take charge of the Clinical Research Unit at the Hall Institute and that Mavis Freeman, who had been my lab assistant at 2/2 AGH and was one of the witnesses at our marriage, was to be biochemist in Macs team. From 2 to 21 September, 1945, I stayed with my parents in Adelaide, ringing Bobbie in Perth most days. On 21 September, I flew to Perth on a military plane, a Liberator, and Bobbie and I stayed together at the Adelphi Hotel, in the centre of Perth. I hired a small car and spent a wonderful few days exploring the beauties of Southwest Western Australia in spring. Bobbie stayed in Perth until her discharge from the Army on 1 November, 1945, after 2,122 days service, outside Australia for 696 days. I had been posted to the 115th Heidelberg Military Hospital on 19 October, so at the conclusion of my leave I went back to Victoria. I spent most of my spare time reading the most comprehensive book on viral diseases of humans, van Rooyen and Rhodes (1948), and anything that I could get on ectromelia virus, since this was to be what I would work on with Burnet. Eventually, on 31 January, 1946, I was discharged from the Army, with 2,059 days service, outside Australia for 1,086 days. I started work at the Hall Institute on 1 February. We had found a suitable flat in Milswyn Street, South Yarra, just opposite the southern entrance to the Royal Victorian Botanic Gardens. I developed the habit of walking through the Gardens and along the bank of the River Yarra to Elizabeth Street, where I would catch a tram to the Hall Institute, which was located in a wing of the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Initially Bobbie worked part-time in the Alfred Hospital, just to the south of our flat, where her best friend, another Western Australian nurse, Jean Freeman, was working. Later, Bobbie joined me as an unpaid technical assistant. Andrew, R. R., Bonnin, J. M. and Williams, S. E. 1946, Tick typhus in Northern Queesland. Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 2, pp. 2538. Bonnin, N. J. and Fenner, F. 1941, Local implantation of sulphanilamide for the prevention of gas gangrene in heavily contaminated wounds: a suggested treatment for war wounds, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 1, pp. 13440. Boyd, J. 1966 Neil Hamilton Fairley, 1891 1966, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society, vol, 12, pp. 12341. Fenner, F. 1946, The epidemiology of North Queensland tick typhus: Natural mammalian hosts, Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 2, pp. 6668. Fenner, F. and Jackson, A. V. 1946, Enteric fever due to Salmonella enteritidis var. blegdam (Salmonella blegdam): a series of fifty cases in Australian soldiers from New Guinea. Medical. Journal of Australia, vol. 1, pp. 31326. |